Most of my motorcycles has been subject

for newspaper articles. But only once have I been honoured with a main feature in a Motorcycle

Magazine.

Jaqueline Bickerstaff was our guest for a few days as overseas secretary of

HRD/Vincent Owners Club |  |  This feature was printed

in the October issue of the magazine in 1995 This feature was printed

in the October issue of the magazine in 1995 |

|

Ding dong bell,

something's in the well,

- but it's not a cat.

In Norway Jacqueline

Bickerstaff discovered a

1936 Indian 750cc Standard Scout that was never a quisling |

| It was the summer of 1941, and Norway was occupied by

the Germans. They were running short of materials and confiscating vehicles built after

1930, which would have included Karl's pride and joy, is 1936 Indian Standard Scout. Rather

than give it up, or help the Germans, Karl hung the Indian down the well of his farm by a

log through its rear wheel; then he covered the well over thoroughly, and left for neutral

Sweden whose border was a mere 35 miles away. It was to be five years before he could retrieve

his bike, which he kept until his death in 1984. Karl Kakneset was born in 1898 but didn't

become a motorcyclist until fairly late in life. He was a tenant farmer until, in 1936,

he finally bought his little farm.

|

|

| Finding there was some money left over from

the transaction, Karl bought an old 600cc Indian Scout. The ageing bike proved a bit slow,

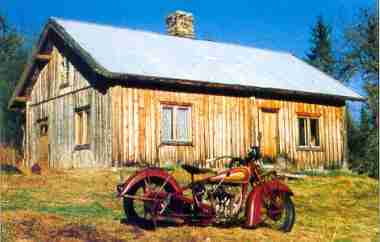

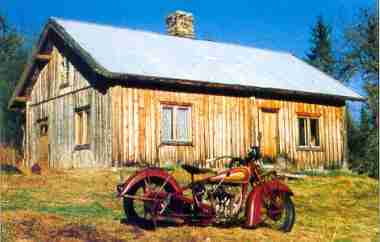

which caused his friends | Karl's first

Scout stands behind his

"pride and joy" 750 Standard Scout,

in front of his

farmhouse |

| some amusement, so that when his sister and brother-in-law,

on a trip to Oslo, left him with their Harley outfit, he went straight to his Oslo dealer

and traded in the old model for a new 750cc Standard Scout. After that, no one could

catch him! |

|

|

|

| Indian leaf sprung trailing link suspension

|

|

For the duration of Norway's occupation, the Indian had to remain hidden until, in 1946,

Karl could return and recover it. Up to 1953 he rode the Indian in Sweden where he worked,

before returning to his farm in Norway to work in the forest and keep stock. The bike was

kept on the road, officially, until 1958 when he handed his plates in. But he enjoyed

showing the Indian off to youngsters until the day when someone stole the Chief front

lamp, of which he was so proud. Thereafter, he hid the bike away and became increasingly

reclusive - even to the point of chasing people away with a gun. In 1968, Karl asked at

the revenue office whether he needed to declare the old bike as an asset.

Luckily, a motorcycle friend only intrerested in Triumphs were handling the declaration

and was invited on a visit. He asked, Per Erik, who was already seeking out old bikes

from all over Norway, to come along. Later he visited Karl, gave him rides in his car and

listened to stories of the old days since his work was close by. The bike was not for sale,

and the old man still regarded the Indian as his pride and joy, so much so that when a

curator from the social service called at Christmas 1984, he found he had to help Karl with

the rest of manhandling it from the shed and into to his kitchen! He had already spent two

days hauling it through the deep snow. Sadly, it was only a

few days later that Karl suffered a fall and spent two days lying in the snow before

being found. He had been a strong man, but this proved too much for his constitution

and he died in hospital at the age of 86. Karl's nephew knew of Per Erik's friendship

with the old man, as well as his enthusiasm for motorcycles and, therefore,

offered him to buy the Indian. |

|

| The Scout was

a never restored, oneowner machine so, naturally, Per Erik snapped up the offer.

But, there was another pleasant surprise to come. Together with the Indian's papers, Per Erik found

some from Karl's little old Indian which he had kept for such a short time. It turned out that

these papers matched the numbers on a dilapidated 600cc Scout that Per Erik had

salvaged from Hamar. He had both of Karl's old bikes! By the 1930s, American motorcycles

had grown big and heavy and, in truth, the Scout was not the Scout of old but a redesigned

(and cheapened) 750 Scout engine in the bigger Chief frame. With a foot clutch and

left-hand twist grip to cope with, I was a little apprehensive about my first

ride but, fortunately, Norway is thinly populated and there isn't much traffic outside

urban areas. |

|

| The Standard Scout is a genuine one-owner,

unrestored machine, seen here outside Karl's old farmstead; note old tyre by the door

|

|

|

| But first, I had to start it! Not that the Indian should be difficult, with a modest

compression ratio and coil ignition, but should you sit astride the. bike or start it from

the side? Per Erik - and all the books say from the side, but I am used to being astride

my bikes. Well, I continued to do it my way, but I can tell you that from the side is better

for the Indian aficionado. |

|

| Karls old 600 cc

IndianScout, now owned by Per Erik Olsen along with the later Standard Scout. It's

not a runner |

| Why? Because the inside

of your thigh catches the pansaddle frame and, with all one's weight behind the kick, it hurts.

For my first take-off I pushed the Indian into the road, facing straight ahead, before attempting to pull

away. The clutch began to take up fairly controllably, but finished with a bang -probably much more so

than when new and well adjusted. The heavy flywheels generally looked after things so that it didn't

prove much of a problem, though I never got to be slick with it. Gear changes were no problem, though a

bit slow. Roll both grips away, press the clutch pedal, haul on the gear lever with the right hand,

then push the clutch pedal back and roll the grips towards you. Unusually for a hand-change bike,

the throttle hand (left hand) is in control throughout; the

right-hand grip only controls the ignition advance. |

|

Once underway, the bike wasn't as heavy as I had

expected. Throttle response was poor and ignition response vague, suggesting stiff cables and loose

pivots at the throttle butterfly and ignition distributor. Every indication, however, was that this

was a result of wear and non?use, rather than being inherent. |

|

With a little more speed and throttle, the engine ran surprisingly strong and at lower speeds gave

a lovely vee-twin exhaust note, too. It was very flexible and quite happy to cruise at anywhere

between 30mph and 60mph, I would guess, although there was no speedometer to check against. At

higher speeds, I can understand why American models were popular in Norway before the war. Like

the Americans, they had a sparsely populated country with primitive roads, and long distances between

towns with few facilities. Sturdy and fairly fast bikes, with fat tyres, were well suited to

these conditions and the low traffic density did not require quick handling or stop-on-a-sixpence

braking. Ah, braking. The manufacturer's advertising was adamant that Indian brakes did not grab, and I

assure you that grab they do not. |  | |

The Standard Scout used a redesigned enlarged Scout engine in the new Chief frame

|

|

|

|

| Dirt roads are

still common in rural Norway and the Indian still copes with them admirably |

| Haul on the front brake lever as you will, it doesn't grab;

the right hand, then push the clutch pedal back and roll the grips towards you.

in fact, it doesn't do too much to stop the bike, either, although the rear brake (which is of

a similar size) is reasonably effective. Since the drums are quite large, I would put the braking

performance down to o1d age and wear were it not for the fact that contemporary road tests echo

my own conclusions. On Norwegian country roads there was little need for harsh braking,

so only on a single occasion

was I made fully aware of this limitation. I was just getting the feel of the Indian, and

approaching an interesting twisty section, when I realised that the tarmac surface gave way

to dirt between me and the bends. I couldn't scrub off the speed quickly enough and went in

faster than I would have wished, expecting things to get quite lively. All it actually proved

was that the big American bike handled better than I had expected. |

|

|

|

|

The fat tyres absorbed bumps and washboard surface surprisingly well, and the heavy rigid frame

remained stiff and true. I began to really understand why the Norwegians had favoured the big

Harleys and Indians. Riding to Karl's farm involved more dirt roads, followed by the farm track,

but the only time the Indian became a real handful was when I rode around in front of his old

house for the camera, as there were numerous rocks hidden in the grass to bounce over!

During the riding shots, the modestly finned side-valve became quite hot, but continued to run

as well as the sloppy controls would allow. But later, on the open road, it began to spit and

pop, running very poorly towards the finish. My conclusion was that rare problem on an old

bike; - too much electricity. |  | |

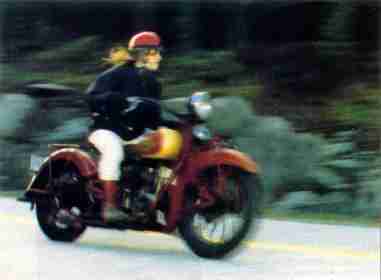

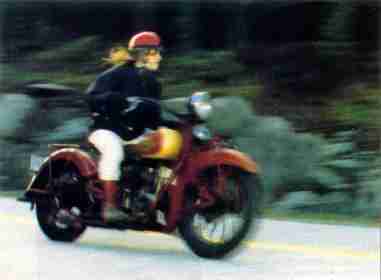

Foot cluych and left hand throttle proved not too fearsome, although

control cables needed attention; sprung seat provided rider comfort

|

|

|

|

| Fun on the open road |

|

I had checked the voltage at one point, finding something like 13 volts

which is just about right for a 12 volt system. However, both the books and the Autolite

generator confirmed that the Indian was running a 6 volt system, so what was up? Well, the

original specification called for a large, 24 amp? hour battery whereas Per Erik had

only an ordinary, and old, standard (about 12 ah) item which the substantial dynamo

easily overloaded with its crude "third brush" regulating system. Joe Lucas

could have learned a lot from Mr Autolite! The battery was fairly thoroughly "dead" and,

even if this didn't harm the ignition system, no doubt it caused plenty of misfiring

or points burning. A pity, because the Indian could be so nice when running well. |

|

|

Per Erik has some beautifully restored machines in his garage, a Henderson and one

of the earliest post-war Vincents among them. Fortunately, he has no intention of

restoring the Indian. It would be a travesty to destroy an

original machine with such a history, to create some better-than-new concours machine; of

that we are greed. However Per Erik is reluctant to do anything more than necessary to keep it

barely running, even though he has ridden it on one or two long runs. |

|

|

If it were mine,

I would undertake a little more refurbishment to get the controls, carb and ignition

working smoothly, as well as the lights repaired. It would be such a pleasure to ride, then.

In the early days of the US motorcycle industry there were numerous manufacturers,

such as Yale, Thor, Cyclone, as well as better remembered marques, like Henderson

and Excelsior.The two big names are, of course, the still-surviving Harley Davidson

and, at one time the largest manufacturer of them all, Indian. It is perhaps fitting

that so many Indians survive in Scandinavia, because Oscar Hedstrom, one of Indian's

most famous designers, was Swedish, and the company employed many Scandinavians in

their Springfield machine shops. In 1911, Indians were some of the most advanced

and fastest bikes around, as they proved

by humiliating the British industry with a 1-2-3 in the Isle of Man TT. By 1937 they were

big and heavy bikes, typical of late American practice and that is clearly visible in this

Standard Scout, its engine looking a little lost in the frame designed for the 1000cc

Chief. The buyers and dealers of the time thought so, too, and it never achieved the

reputation of the earlier 101 Scout of circa 1928. All the same, the Standard Scout quite

impressed me, denting my patriotic bias for British machines. I look forward to the day

when I can sample one of those nimble 101s, or maybe a big Indian Chief. |

| |

Norway's road system was similar to thew USA's and American Bikes proved

ideal for tackling poor surfaces and long distances

|

|

|

|

SPECIFICATION 1936 INDIAN STANDARD SCOUT |

|

ENGINE |

TYPE | 42 degree vee-twin side valve |

BORE & STROKE | 73 x 89mm |

CAPACITY | 745 cc (45 cu.in. |

COMPRESSION | n/a |

POWER | 25 bhp approx |

CARBURATION | mm |

|

TRANSMISSIOM |

CLUTCH | Multiplate, foot operated |

GEARBOX | 3 speed |

RATIOS | 4,66 6,45 11,5 :1 |

PRIMARY DRIVE | Quadruplex chain |

FINAL DRIVE | 5/8" x 3/8" chain |

|

|

| ELECTRICAL |

IGNITION | Coil / distributor |

GENERATOR | Autolite 6 volt, 3 brush |

LIGHTING | 7 in headlampm, 6V 24ah battery |

|

CYCLE PARTS |

FRAME TYPE | Duplex,brazed lug |

SUSPENSION | |

front | Indian Leaf spring, trailing link |

Rear | Rigid. |

WHEELBASE | 61,5 in |

SEAT HEIGHT | 29 in |

GROUND CLEARANCE | 6 in |

WEIGHT | 430 lb |

TYRES | 4,00 - 18 front and rear |

BRAKES | 7,5 drums front and rear |

FUEL TANK | 3 gallons |

OIL TANK | 4 pints |

|

| PERFORMANCE |

TOP SPEED | 75 - 80 mph |

ACCELERATION | satisfactory |

FUEL CONSUMPTION | 50 mpg |

|

HISTORY |

MANUFACTURER | Indian Motocycle Company, Springfield Massachusetts |

PRICE NEW | £ 95 in UK |

MODEL LIFE | 1932- 1937 |

OWNER | Per Erik Olsen, Kongsvinger, Norway |

|

| | |

|

|

|

|